Imagine Dr. X, your supervising leader, pulls you aside after a meeting in which you presented and says, “I want to give you some feedback.” There is displeasure in his posture and condescension in his tone. It doesn’t take deductive reasoning or Spidey-like senses to know he disliked your performance. The alarm bells of your sympathetic system ring loudly in your head as he critiques your presentation, ending with “Don’t do that again” and “Do it better next time.”

Dr. X walks away, thinking his words were helpful and that next time, you will get it right. You, on the other hand, didn’t find Dr. X’s opinion the least bit helpful, start making a mental list of his shortcomings, and ruminate on how not to do “that” again. Whatever “that” is.

How is that Dr. X (aka The Giver) views the conversation as delivering honest feedback while you (aka The Receiver) see it as intense and pervasive criticism? There are two main reasons. One – few are skilled at giving feedback that actually helps someone to excel. Two – receiving feedback well, especially when unsolicited, is also a learned skill that few possess.

We know that feedback is wildly important to the learner mindset, and that feedback is everywhere. It’s in the clinic, in the operating room, in your social media account, in the hallway with Dr. X, and it’s even in your home. So, if feedback is everywhere, and it is good for us, why can it be awkward and dreadful to receive? Or what was once true for me, why did I reject the that idea feedback was a gift, and instead ranked it up there with getting a root canal?

In taking a closer look at the art of giving and receiving feedback, physicians are somewhat notorious for not providing valuable feedback to one another and for not holding one another accountable in a supportive manner. Conversely, we may rebuke or internalize feedback as an objective assessment of our ability because it is unnatural or intensely harsh, or a combination of each.

Likewise, positive feedback that does nothing more than tell us what we want to hear and feed the glutenous ego (e.g., great job!) does not teach us how to do our work more effectively. As a physician coach, teaching others about feedback is a core component of my training program, the Malcolm Method. My experience coaching other physician leaders broadens both their perceptions of feedback, and my own. Here’s what I have come to learn about feedback.

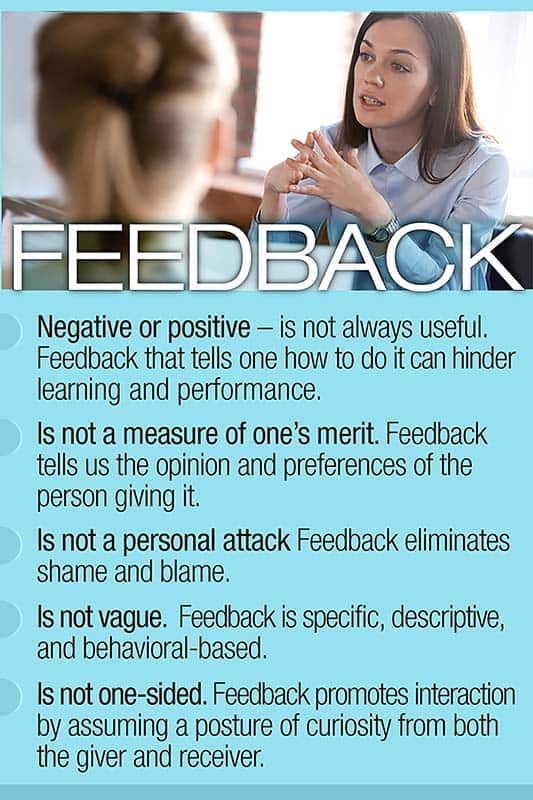

- Feedback – negative or positive – is not always useful. Feedback that tells one how to do it can hinder learning and performance.

- Feedback is not a measure of one’s merit. Feedback tells us the opinion and preferences of the person giving it.

- Feedback is not a personal attack. Feedback eliminates shame and blame.

- Feedback is not vague. Feedback is specific, descriptive, and behavioral-based.

- Feedback is not one-sided. Feedback promotes interaction by assuming a posture of curiosity from both the giver and receiver.

Empowered by a new perspective, I set out to get especially good at receiving and giving feedback. I focused first on how to receive feedback well since feedback plays a crucial role in one’s development and eliciting feedback is a necessary part of learning.

Receiving feedback well means engaging in the conversation skillfully and making thoughtful choices about whether and how to use the information. I decided to seek out feedback, rather than waiting for it to find me. I sought input about the effectiveness of my leadership style, especially its impact on others, my intended audience. I put on my explorer’s hat and remained open to the process by silently asking myself:

- How well do I know the other person? Is this someone I trust or respect?

- What is the other person trying to tell me? Am I staying present and listening?

- How can I be curious about the message? Am I attached to the positive or the negative parts of the message?

- What is of use to my development? What can I discard?

- How can I turn what I learned into action?

From each conversation, I learned how to recognize and manage my emotional triggers as well as the importance of setting boundaries so that I could stay curious and connected. Keeping these questions in mind helped me to get better at receiving feedback, no matter the skill set of the person giving it. In their book, “Thanks for the Feedback,” authors Douglas Stone and Sheila Heen write, “receiving feedback sits at the intersection of two needs – our drive to learn and our longing for acceptance.” I now have a new relationship with feedback, in part because I invite it in and know when to close the door, disinviting it from my party politely. The world is waiting to tell you it’s opinion of you. Are you ready to receive it?

Teresa Dean Malcolm, MD, FACOG, MBA, CPE, is zealous in her belief an exceptional experience in clinical care, the human(e) experience, is achievable through meaningful and authentic relationships with others. She has served in executive positions, integrating people with process and purpose, and successfully aligning the ideas of the team with a compelling vision. Her coaching philosophy, The Malcolm Method, is rooted in trust and supportive accountability. Through thought-provoking conversations, she strives to deepen the awareness of her physician clients and further their actions, thereby helping them to thrive as they lead. Dr. Malcolm (known to her friends and family as Terri) is a loving wife to her husband, Nate. Together they have three charming and athletic boys, Nathaniel, and twins, Roman and Colton.

I think Dr. Malcolm’s insights and overall approach to simplifying and reframing such a complicated (and often challenging personal best practice) is supremely useful and accessible. THANK YOU so much!

THANK YOU, Christopher! The tips are designed to help you be your best self and encourage connection, whatever the circumstance. Glad to know you find them beneficial!